Initially, the sides of the Bent Pyramid were inclined at an angle of about 60°. When structural faults began to appear, however, the inclination was reduced to about 55°. The base had to be enlarged, and an outer layer of casing added. This however, was not enough. When the pyramid reached a height of 45 m (147.6 ft), the builders realized that structural faults were appearing again. Therefore, in an attempt to prevent the structure from collapsing, the builders were forced to reduce the load on the lower structure. This was achieved by reducing the angle of inclination to 43°, which served to reduce the mass of the upper structure.

Snefru’s builders learned from their previous experience, and got it right the third time. The Red Pyramid, known also as the North Pyramid, was the third pyramid built by Snefru. Rising to a height of 105 m (344.5 ft), the Red Pyramid is the highest of Snefru’s three pyramids, and the first true pyramid to have been built successfully by the ancient Egyptians.

The Red Pyramid derives its name from the reddish hue of the red limestone used for the construction of its core. When the pyramid was completed, however, it was covered with white limestone, which would have given it a white, rather than red, appearance. Although most of the casing has since been removed, some still remain, and these provide interesting pieces of information regarding the pyramid’s construction. For instance, some of the casing stones were dated. Using the information, archaeologists were able to estimate that the pyramid was completed in about 17 years.

The Red Pyramid is Snefru’s tallest pyramid and can be found at the Dahshur necropolis in Cairo. (lienyuan lee / CC BY 3.0)

Although the Red Pyramid is the tallest of Snefru’s three pyramids, it is only the third tallest in Ancient Egypt. This is due to the fact that its sides have an angle of 43°. By comparison, the tallest ancient Egyptian pyramid, the Great Pyramid, which stands at a height of 147 m (482.3 ft), has sides that incline at an angle of 51°.

The Pinnacle of Pyramid Building

The Great Pyramid is located in the Giza pyramid complex, and was constructed by Khufu, Snefru’s successor, and the second pharaoh of the Fourth Dynasty. Interestingly, Khufu is mentioned by Herodotus in The Histories. According to the Greek historian, the pharaoh, known to the Greeks as Cheops, was a tyrannical ruler. Apparently, Khufu “closed down all the sanctuaries, stopped people performing sacrifices, and also commanded all the Egyptians to work for him.”

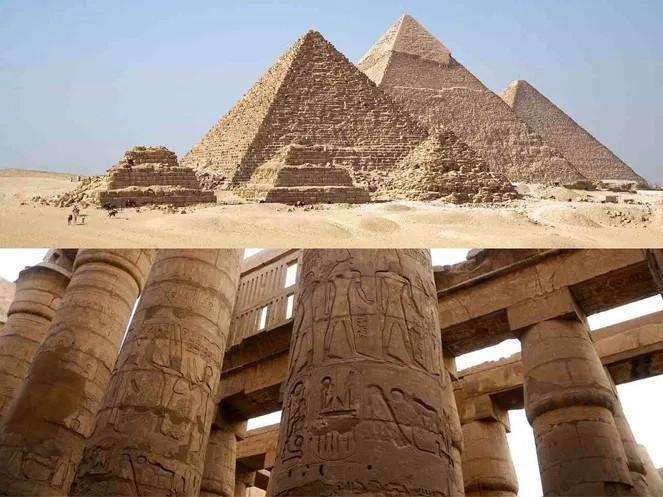

The Great Pyramid of Giza or the Pyramid of Khufu (center), Pyramid of Khafre (left), Pyramid of Menkaure (right) and the Pyramids of Queens (foreground). (sculpies / Adobe stock)

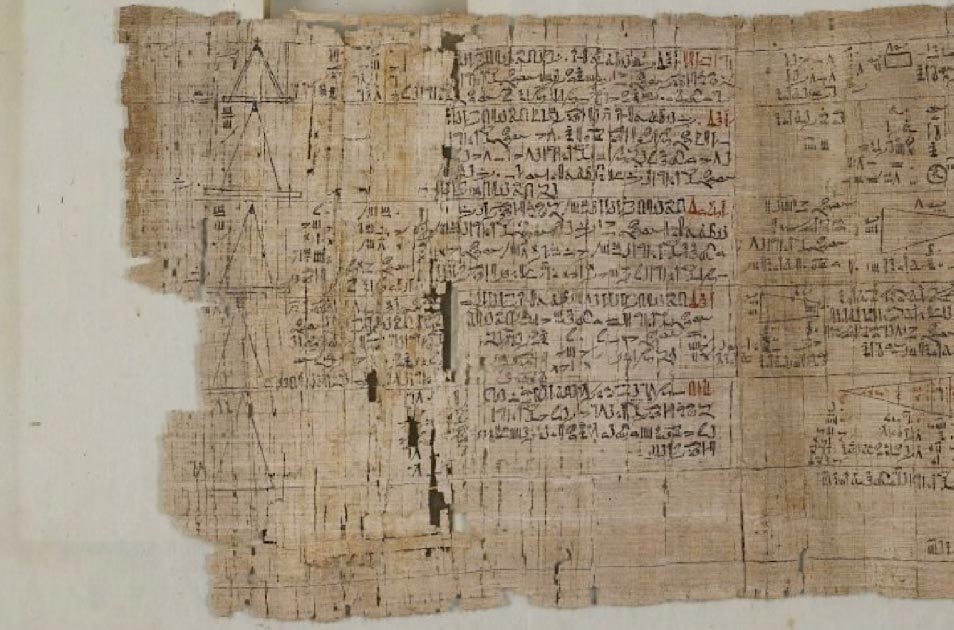

In the Westcar Papyrus (written during the Hyksos period, but recounting tales that were probably written during the Middle Kingdom), on the other hand, Khufu is presented in a more positive light. In this work, the pharaoh is depicted as a wise, generous, and inquisitive ruler.

In any case, the Fourth Dynasty is considered to be the height of pyramid building. Apart from Snefru’s three pyramids, and Khufu’s Great Pyramid, the pyramids of Khafre and Menkaure were also built during this period. One of the factors contributing to the success of such massive construction projects is the high degree of centralization achieved by the pharaohs of that dynasty. The pharaohs took measures to maintain their power.

For example, high officials were granted estates scattered around Egypt. This served to prevent the formation of local centers of influence. At the same time, however, the intensive exploitation of the land could be encouraged. Apart from that, Egypt enjoyed a long period of stability and peace. The country was not seriously threatened by any foreign power, whilst the pharaohs, who wielded absolute power, provided a stable government at home. This meant that large amounts of resources could be allocated for pyramid building.

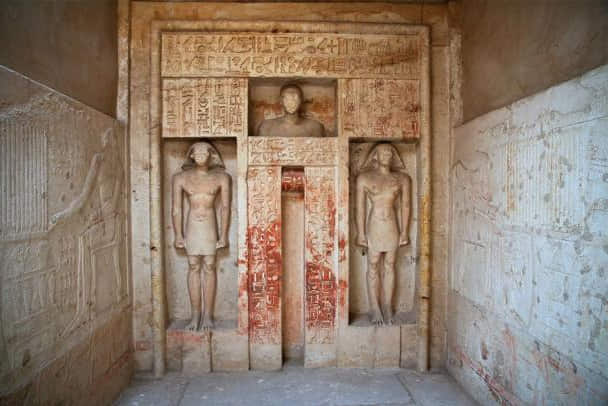

The construction of a pyramid was not an end in itself. Instead, pyramids were meant to serve as cult centers for deceased pharaohs. The royal funerary cult was supposed to provide for the needs of the dead king in the afterlife, and was meant to continue indefinitely. Khufu’s funerary cult, for instance, was maintained as late as the Twenty-sixth Dynasty. Indirectly, this cult also sustained the living, especially those who were involved in its maintenance.

Most of the offerings presented to a deceased pharaoh did not end up on his altars or offering tables, but was consumed by the priests maintaining the cult, or distributed more widely. Although the building of pyramids lost its popularity after the Old Kingdom, the concept of the royal funerary cult survived, and its practice continued in later periods.

Significant Changes Came With the 5 th Dynasty

The prosperity of the Fourth Dynasty, however, did not last forever. The Fourth Dynasty ended around 2494 BC, and was replaced with the Fifth Dynasty. A number of changes can be detected between the Fourth and Fifth Dynasties. For a start, the pyramids of the latter are noticeably smaller and less solidly built than the ones of the former.

The Pyramid of Userkaf (the founder of the Fifth Dynasty) at Saqqara, for instance, is only 48 m (157.5 ft) in height, and lies largely in ruins today. One of the possible reasons for this is the steady decline of the pharaohs’ wealth. This may be associated with the rulers’ gradual loss of absolute power, another significant difference between the Fourth and Fifth Dynasties. The pharaohs of the Fifth Dynasty had to compete for power with the god Ra (or more appropriately, the priests who served him).

The Pyramid of Userkaf in Saqqara, which can clearly be seen to be smaller than pyramids from earlier dynasties. (Leonid Andronov / Adobe stock)

Ra emerged as an important god during the Fourth Dynasty. At least from the time Djedefra, Khufu’s successor, the pharaohs of the Fourth Dynasty claimed to be the ‘Son of Ra’. It was, however, during the Fifth Dynasty that the cult of Ra reached its zenith. The pharaohs of this dynasty built many sun temples to the god, some of which were lavishly endowed. As a consequence, the priests of Ra attained immense influence in Egypt.

The power of the pharaoh was further eroded by high officials. Whereas the majority of high-ranking officials during the Fourth Dynasty were relatives of the pharaoh, those of the Fifth Dynasty were not. This meant that power was progressively being lost by the pharaoh, and finding its way into the hands of nomarchs, who were provincial governors.

The End of the Old Kingdom and its Legacy

The last significant pharaoh of the Old Kingdom was Pepi II, the penultimate ruler of the Sixth Dynasty. He ascended the throne at the age of six, around 2278 BC, and, according to tradition, reigned for a total of 94 years. Pepi’s pyramid at Saqqara is the largest of the Fifth and Sixth Dynasty pyramids, though a dwarf compared to the ones of the Fourth Dynasty. Pepi’s pyramid was also the last monumental construction project of the Old Kingdom.

Despite Pepi’s extraordinarily long reign, it was clear that Egypt was in decline. The Old Kingdom is considered to have collapsed not long after Pepi’s death. The last pharaoh of the Sixth Dynasty was Nitiqret, whilst the names of most of the rulers of the short Seventh and Eighth Dynasties are lost to history. The Old Kingdom’s collapse was caused by a combination of factors, including the loss of centralization, the increase in the power of the nomarchs, and the growing pressure and hostility of the Nubians to the south.

The Old Kingdom is no doubt an impressive period in ancient Egyptian history, and its appellation ‘Age of the Pyramid Builders’ is an appropriate one. Nevertheless, the end of the Old Kingdom was not the end of the civilization in Ancient Egypt. Although the succeeding First Intermediate Period is often considered to be a period of decline, it is not without its achievements. Moreover, some of the concepts and practices of the Old Kingdom did not disappear, but were maintained by the rulers of later dynasties.