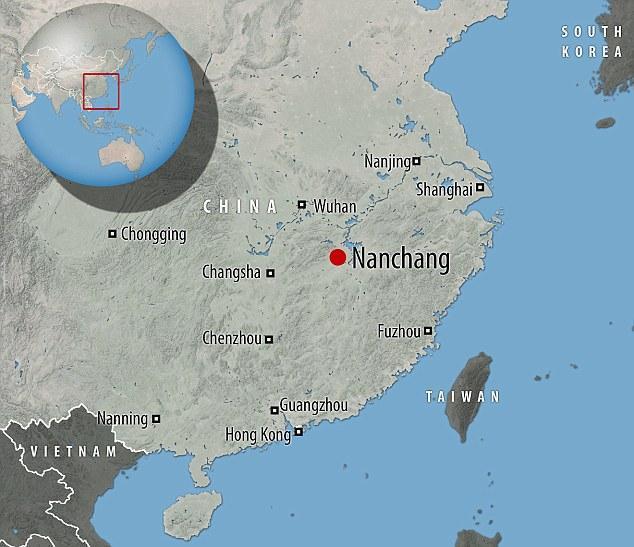

In the Xinjiang District of China, an ancient complex of tombs has yielded over two million copper coins, as revealed by archaeologists’ excavation.

The 2,000-year-old mound, which bears Chinese symbols, characters, and a square hole in the center, was found at a dignified site in the city of Nanchang.

The value of the coins is said to be around £104,000 ($157,340), and experts believe the main tomb belongs to Liujia He, the grandson of Emperor Wu, the greatest ruler of the Han Dynasty.

Archaeologists have unearthed more than two million copper coins from an ancient complex of tombs in the Xinjiang District of China.

The dynasty ruled between 206 BC and 25 AD.

Experts hope the discovery, which also includes various artifacts such as gold, bronze, and iron items, ceramics, bamboo slips, and tomb figurines, may shed more light on the life of nobility from ancient times.

The find follows a five-year excavation process on the site, housing tombs and a burial ritual area, covering an area of almost 9,690 square feet (900 square meters) with walls stretching almost 430,550 square feet (40,000 square meters). The complex may hold valuable insights into the burial practices of the Han Dynasty.

Xin Lixiang of the China National Museum said the next step is to look within the tomb for items that will give a clearer idea of the occupant’s status and identity.

“There may be a royal seal and jade clothes that will suggest the status and identity of the tomb’s occupant,” he said.

Chinese people started using coins as currency around 1,200 BC, where instead of trading small farming implements and knives, they would melt them down into small round objects and turn them into coins for ease of use in transactions.

The “hole money” referred to the coins known as ‘knife money’ or ‘spade money’, and as peculiar as it may sound, these coins were often cast to resemble various farming tools, including spades and knives. The holes in the coins meant they could be easily strung together for transportation and handling.

The hole in these coins served the purpose of stringing them together for ease of use. Typically, around 1,000 coins were strung on a single string for practical storage and transportation.

The ancient money, which bears Chinese symbols, characters, and a square hole at its center, was found at a dig site in the Xinjiang District, in the capital of East China’s Jiangxi Province, Nanchang.

The hole meant that the coins could be strung together to create large chains or to create large amounts of currency. At face value, they would be valued at around £104,060 ($157,340), but because of their age and historical relevance, they were expected to be worth much more.

A single coin can, in fact, sell for thousands of pounds, although at the time, these coins had a very low face value. The Western Han was regarded as the first unified and powerful reign in Chinese history.

While there are many theories about the functions of the holes in the coins, recent research suggests human interaction with the environment played a crucial role in their creation. A census taken by China in 2 AD suggests that the area around the dig site was densely populated, with an average of 122 people per square kilometer, or approximately 9.5 million people living in the flood’s path.

By AD 20-21, the developed region had become the center of a rebellion that would engulf the entire reign of the Western Han Dynasty’s five-century reign of power.

Along with the tons of coins found were also chimes, bamboo slices, and tomb figurines, all of which accompanied the deceased nobles of the past when they were buried underground. The items discovered help fill in more gaps as historians try to complete the puzzle of ancient Chinese burial customs.