It has been speculated that prior to Amenhotep’s construction of Luxor Temple, an older temple stood on the site. The temple or shrine may have been built during the earlier part of the Eighteenth Dynasty, perhaps during the reign of Hatshepsut, if not before. All that is left of this older structure is a small pavilion. Amenhotep enlarged this old temple or shrine, and had the new structure dedicated to Amun.

Luxor Temple was also known by the ancient Egyptians as ipet resyt (which translates to mean ‘Southern Sanctuary’). This is meant to distinguish Luxor Temple from Karnak Temple, which is situated about 3 km (1.86 mi) to its north. The two temples were once connected by the Avenue of the Sphinxes, a processional road lined with sphinxes on each side. The road may have been originally built by Hatshepsut, and Amenhotep added ram-headed sphinxes along its length. Much later, human-headed sphinxes were added by Nectanebo I, a pharaoh of the Thirtieth Dynasty, during the 4 th century BC.

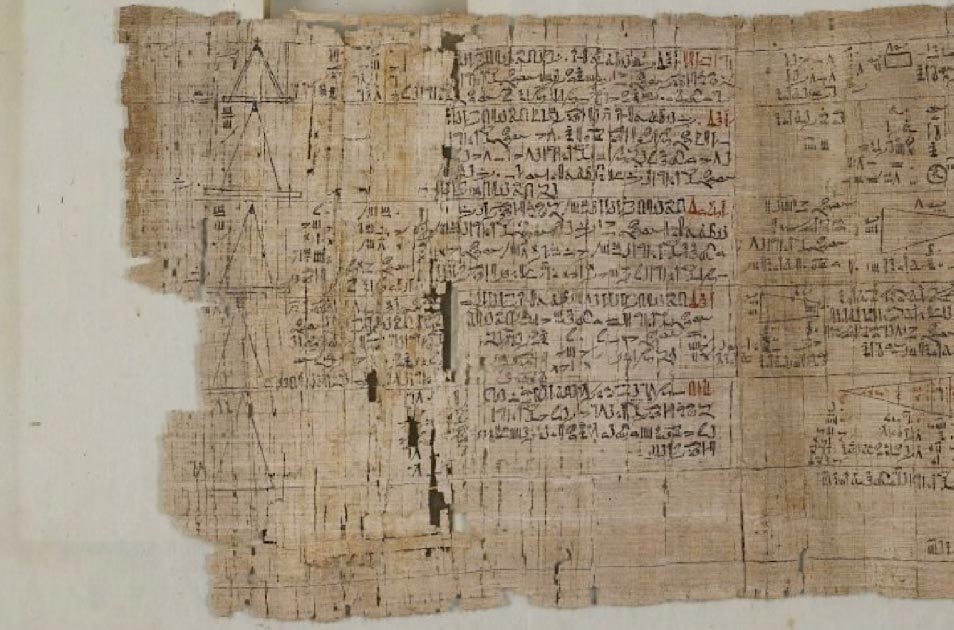

The avenue of sphinxes on the road from Karnak Temple to Luxor Temple, Egypt, where the ritual journey of the Opet Festival took place. (tynrud / Adobe stock)

The Opet Festival: From Karnak to Luxor

In addition to the Avenue of the Sphinxes, Luxor Temple and Karnak Temple are connected by the Opet Festival. The festival is known formally as the ‘Beautiful Feast of Opet’, and Opet is believed to be a reference to inner sanctuary of the Temple of Luxor. The festival was celebrated each year during the second month of the Egyptian lunar calendar. This was the time of the Nile’s inundation, and hence a cause for revelry.

The Opet Festival also functioned as a way for the pharaohs of Eighteenth Dynasty to celebrate their consolidation of power. The length of the festival increased as time went by. During the reign of Thutmosis III in the 15 th century BC, for example, the Opet Festival lasted 11 days. By the Beginning of Ramesses III’s rule in 1187 BC, the festival lasted 24 days. By the time of his death in 1156 BC, the festival lasted 27 days.

The highlight of the Opet Festival was the ritual journey of the Theban Triad (Amun, Mut, his consort, and Khonsu, their son) from their shrines at Karnak Temple to Luxor Temple. Thanks to depictions of this journey on several ancient Egyptian monuments, we have an idea of how it was carried out.

One of these monuments can be found on the south side of Hatshepsut’s Red Chapel at Karnak Temple. Incidentally, this is also the oldest depiction of the Opet Festival that we know of. The reliefs on this monument show that at this time, only Amun made the journey from Karnak to Luxor.

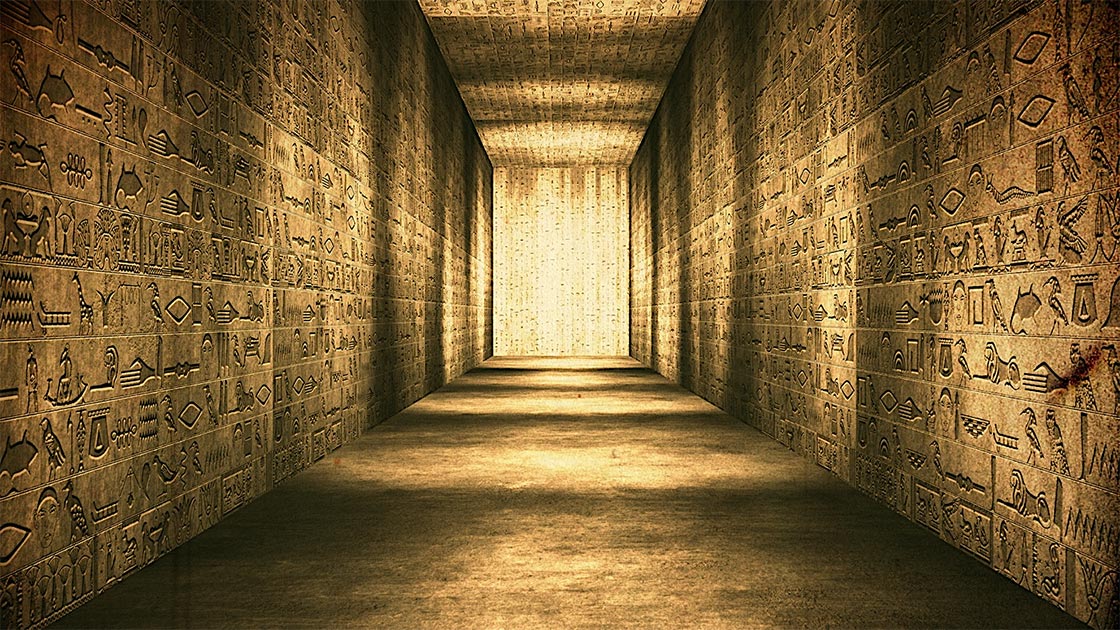

Hatshepsut’s Red Chapel at Karnak Temple. (camerawithlegs / Adobe stock)

The gods shrine was carried by priests, who travelled by foot along the Avenue of the Sphinxes. On the way, they would stop at six altars constructed by Hatshepsut along the avenue. After staying in Luxor for some days, the priests and the shrine would return to Karnak by boat.

As a comparison, scenes of the Opet Festival from the colonnade of Luxor Temple, which were carved during the reign of Tutankhamun, show that by this time, Amun was joined by Mut and Khonsu on his annual journey from Karnak to Luxor. In addition, the reliefs show that the gods were carried in boats through the streets of the city, after which they were loaded onto river barges for their voyage to Luxor. After staying in Luxor Temple for 24 days, the deities return to their home in Karnak Temple via the same route. The city celebrated whilst the gods resided in Luxor Temple.

Relief at the Luxor Temple depicting the Opet Festival procession. (kairoinfo4u / CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Constructions Through the Ages

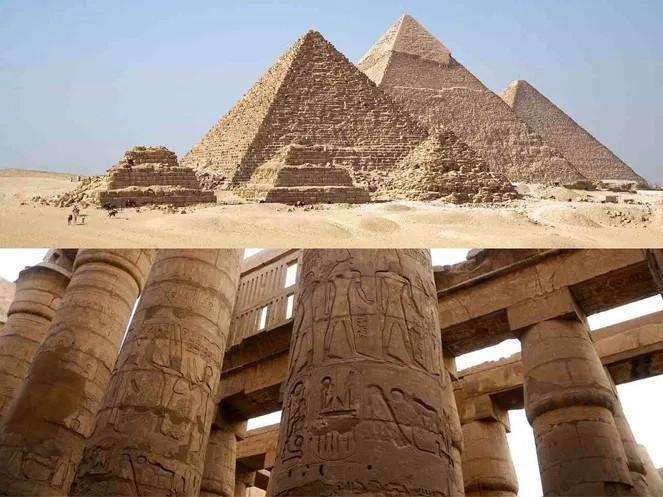

Although the construction of Luxor Temple began during Amenhotep’s reign, it was only completed during that of Tutankhamun’s. At the time of its completion, Luxor Temple included the Avenue of the Sphinxes, two courtyards, a processional colonnade, and the inner sanctum, where the chapels of Mut, Khonsu, and Amun are located. Subsequent pharaohs added their own touches to the temple complex. Amenhotep’s successor, the enigmatic Akhenaten, for instance, built a sanctuary dedicated to the Sun god, Aten, next to Luxor Temple. The structure, however, was later demolished by Horemheb.

The pharaoh who made the most impressive additions to Luxor Temple, however, was Ramesses II, the 3 rd pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty, and perhaps the most famous ruler of ancient Egypt. During his reign, which lasted from 1279 to 1213 BC, Ramesses built the first pylon, which became the entrance to Luxor Temple.

This was also a large advertisement board for the pharaoh, as Ramesses decorated it with scenes of his military exploits, most notable of which being the Battle of Kadesh. Ramesses also added six colossal statues of himself – two seated and four standing, at the temple’s entrance. Apart from the first pylon, Ramesses demolished the first courtyard, which was built by Amenhotep, and replaced it with his own. Ramesses replaced a number of giant statues of Amenhotep with his own.

Statues of Ramesses II at the Luxor Temple. Photo taken on a recent Ancient Origins trip to Egypt. (Courtesy of Ioannis Syrigos)

The importance of Luxor Temple as a religious center is evident in the fact that modifications were made to the complex even after the New Kingdom. For instance, Taharqa, a fourth Nubian pharaoh of the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty (the last dynasty of the Third Intermediate Period), built a shrine to the goddess Hathor, whilst his predecessor, Shabaka, constructed a colonnade. Both of these structures, however, have since been destroyed. The Nubian rulers also added scenes of their military victories onto Ramesses’ first pylon.

After the conquest of Egypt by the Greeks, the chapel of Amun was rebuilt by Alexander the Great, and the Greek ruler is portrayed as an Egyptian pharaoh. Even the Roman emperor Hadrian built something at Luxor Temple. He is recorded to have constructed a small mudbrick shrine dedicated to Serapis. The shrine, however, no longer exists, and all that remains is a statue of Isis and some rubble.

Some of the many ancient columns at the Luxor Temple in Egypt. Photo taken on a recent Ancient Origins trip to Egypt. (Courtesy of Ioannis Syrigos)

Loss in Significance and Revival: Romans, Christianity & Islam

In spite of Hadrian’s small shrine, by the Roman period, the religious importance of Luxor Temple had already been significantly reduced. Instead, the Romans saw the temple complex as a convenient location to build a fort, one of the reasons being the availability of raw materials. Some of the masonry from the temple were used by the Romans for the construction of their military buildings. In addition, the size of the temple complex could accommodate a large garrison, and it has been estimated that up to 1500 Romans were stationed in that fort.

Still, Luxor Temple did not really lose its religious significance entirely. Instead, it would be more appropriate to say that the Theban Triad worshiped by the ancient Egyptians were simply replaced by new ones. For instance, during the Roman period, the temple was rededicated to the cult of the emperor.

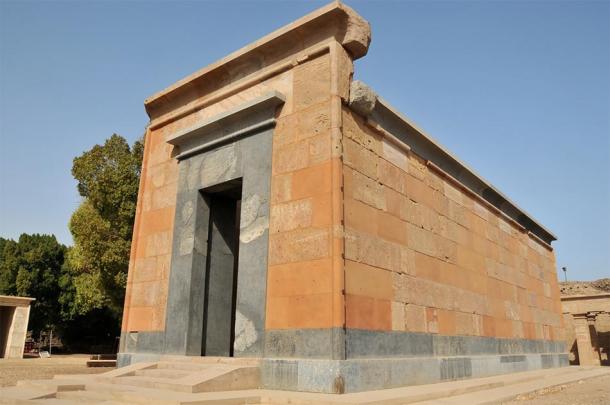

Later on, when the Roman Empire adopted Christianity, Christian churches were built around the temple. In fact, one of these churches was built inside the temple itself, in Ramesses’ courtyard. After Egypt was conquered by the Arabs, this particular church was turned into a mosque, which is still standing today. This mosque, known as the Mosque of Abu Haggag, is named after a local holy man by the name of Youssef.

The Mosque of Abu Haggag can be seen in the courtyard of Ramesses II at the Luxor Temple. (inigolaitxu / Adobe stock)

Youssef is believed to have been from Damascus, moved to Mecca during his forties, and finally migrated to Luxor, where he lived for the rest of his life. In Luxor, Youssef preached Islam to the local population, and it is claimed that the mosque was built by the holy man himself. Youssef also gained a reputation for taking care of pilgrims who were on their way to Mecca, and hence received the title ‘Abu Haggag’, which means ‘Father of Pilgrims’.

According to a local legend, after Youssef had built the mosque in the courtyard of Luxor Temple, a high-ranking official wanted to remove it. Although Youssef protested, the official was determined to demolish the mosque. One morning, the official woke up, and found that his body was paralyzed. He thought that this sudden paralysis was caused by his decision to demolish the mosque. Therefore, he retracted his order. The mosque was saved, and the official recovered from his paralysis. Interestingly, the holy man’s birthday is celebrated each year in early November, and includes a procession of his boat around Luxor. This may be reminiscent of the ancient Opet Festival.

The Mosque of Abu Haggag is still used as a place of worship even today. In addition, archaeological excavations have been carried out at the Luxor Temple. For instance, in 1988, numerous Eighteenth Dynasty statues were unearthed in the temple’s courtyard. Conservation and preservation work have also been done at the site. On top of that, the temple is a popular tourist destination, and the city’s economy benefits greatly from the tourism industry. In 1979, Luxor Temple was inscribed in UNESCO’s World Heritage List, as part of a group known as ‘Ancient Thebes with its Necropolis’.