Construction in York, England underwent a Viking Age town called Jorvik. Archaeological excavations revealed an Anglo-Norse world rich with information about the past.

York sits in northeast England and was founded by Romans around 71 CE, who called it Eboracum. During the Anglo-Saxon period, Eboracum became the center of the kingdom of Northumbria and was known as Eoforwic. Around 865 CE, a Great Viking Army landed in England, and on November 1st, 866 CE, the Vikings conquered York. Upon their successful conquest, the Norse permanently settled Eoforwic, which became Jorvik around 876 CE. Scandinavian rulers maintained control of Jorvik until the expulsion of Eric Bloodaxe in 954 CE. The York Archaeological Trust began excavating the area in the 1970s and uncovered homes and artifacts from the Viking Age.

On a street named Coppergate, archaeologicalists uncovered long, narrow plots divided by wattle fences. The street’s name roughly translates to ‘street of the cup makers.’ Archaeologists did find cup molds throughout the excavation, but excavations of Coppergate also revealed a market that once served as the workplace of Viking Age craftspeople. Fortunately for archaeologicalists, the soils of Jorvik were moist and rich. Oxygen was unable to penetrate these soils; thus, many unique artifacts from the ninth and tenth centuries were perfectly preserved, revealing a world of far more than cups.

Textile often preserves poorly when buried by centuries of earth built up by centuries of accretions of earth built up by centuries of human activities. Archaeologists found a variety of leather shoes belonging to both adults and children during the excavations. Most of the shoes proved to have been made via the turnshoe method. In this form of shoe manufacture, the shoemaker sews the sole and uppers together inside out. Then, the shoe is turned the right way out, thus the name. A different kind of shoe was also found. This shoe was made of a single piece of leather folded around the foot and sewn together. With this unique assemblage of shoes, archaeologists can begin to explore the diversity of shoes worn and investigate which ones may have been imported or made locally.

Archaeologists also recovered fragments of a woolen sock. Studying the sock, they learned that it had been knitted using a single-eyed needle. The wool had faded over the centuries in the earth, and it is not clear what the original color of the sock was, though a red band was evident around the ankle. So far, the Coppergate sock is the only one of its kind found in England. Not even its matching pair has yet been found. The sock is thus a truly unique Viking import.

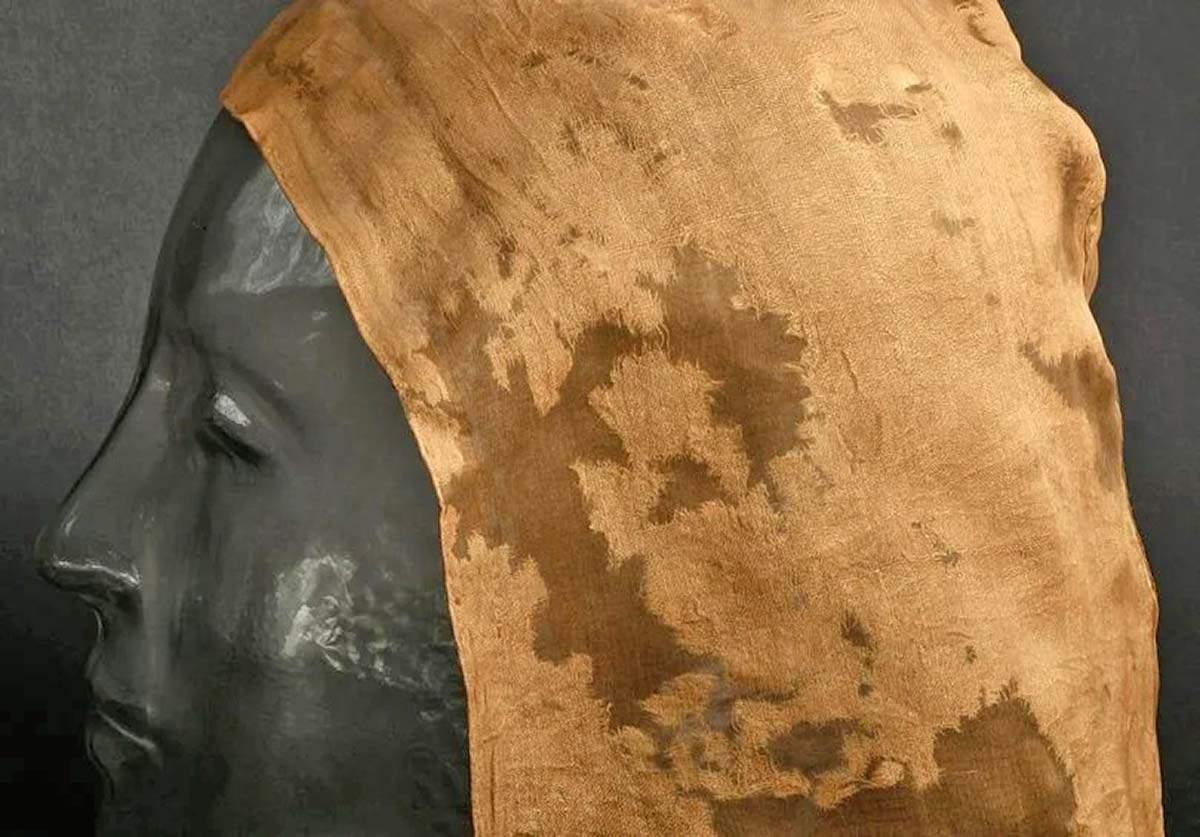

The Vikings remained in York throughout the tenth century CE. Evidence of their occupation has come in surprising forms. In one pit, dated to the end of the tenth century, archaeologists discovered a crushed textile. Scholars smoothed the item and took a closer look at the myriad of stitches where it would have been possible to attach ribbons which could have secured the headdress to the head. There were stitches at the bottom of the headdress where it would have been possible to attach ribbons which could have secured the headdress to the head.

Silk was an exotic textile in the medieval world. Possible sources of the silk include the kingdoms of the Eastern Mediterranean and beyond, like the Byzantine Empire. Another possible source was Baghdad. Other pieces of silk were found throughout Jorvik, suggesting that silk was imported into medieval York and made into various items by local craftspeople. Due to the perceived value of exotic items in the medieval Norse world, the silk headdress likely belonged to a wealthy Viking woman.

As construction efforts in York continued, a mechanical digger hit something hard. Looking closer, investigators found a well-preserved, good-linen hood with an exterior made of iron, glass, and an extraordinary helmet. The helmet consists of iron and copper alloy. Scholars have dated it to the eighth century CE. This artifact thus provides insights into the Vikings’ settlement of York and offers a glimpse into the world of the Anglo-Saxons who also called Jorvik home.

Taking a closer look at the helmet, archaeologists found an inscription in Latin that reads: ‘In the name of our Lord Jesus, the Holy Spirit, and God; and to all we say Amen/Osher/Christ.’ The helmet has been interpreted as both functional armor and a symbol of Anglo-Saxon power.

Excavations at Jorvik revealed some five tons of animal bone, also known as faunal remains. From these remains, archaeologists and zooarchaeologists know that mice and rats scurried around the Anglo-Saxons’ and Vikings’ feet. They caught, traded, ate fish, ducks, and geese roamed the streets, while dogs, cats, and pigs scuttled around medieval homes. Plant or flora remains were also collected from the Viking town. From excavations, archaeologists believe that plant-based foods such as celery, coriander, lettuce, radishes, and parsnips were part of the Viking diet. These artifacts, while less attractive than others, are highly informative and significant to scholars’ understanding of the Viking world.

The silk headdress was not the only item with Eastern roots that found its way to Jorvik. The Vikings had traded routes with the Baltic as well. In Jorvik, archaeologists found traces of amber from the Baltic. As with the silk, the amber seems to have been imported and then molded by York-based craftspeople. They manufactured rings, pendants, and beads.

Amber was a popular material for adornment in the Viking Age, but it may have been more than decorative. One archaeological suggestion is that amber emitted a static charge or smell that the Vikings saw as a sign of magical power.

Another interesting artifact they found from the east was a cowrie seashell. Shells occur around the world, but this shell was of the species Cypraea pantherina. That species of shell occurs naturally in the Red Sea only. Cowrie shells were used as currency in various parts of the world and were highly valued. The presence of cowrie shells in Viking-age York suggests connections to eastern trade networks.

Coins discovered in Jorvik came from many different regions. One coin was made in present-day Uzbekistan around 903-908 CE. Analyzing the source of the shell and the coins from the east, archaeologists were able to determine if the Vikings traveled to the Red Sea or present-day Uzbekistan themselves, or if they acquired these objects through exchange with other marauding traders. What seems apparent is that the Vikings maintained interests in objects that could only be acquired in the East.

According to some historians, the Scandinavians who first conquered the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Eoforwic had previously voyaged broadly in Ireland. At Jorvik, evidence of connections with Ireland emerged in the form of copper alloy rings, possibly used to decorate clothing and/or fasten clothing to each other during the Viking Age. These metal rings with pins may have been used to decorate clothing and/or fasten eastern clothing to together during the Viking Age. The rings were found in Ireland in the tenth century.

Although many ring pins were collected during excavations of Jorvik, archaeologists have not yet determined if the ring pins were manufactured in Ireland and imported to Jorvik, or if Jorvik-based craftspeople made them to imitate the Irish style. What is clear is that Jorvik maintained connections to the west, leaving a deep impression.

Archaeologists recovered an abundance of artifacts that seem to indicate the Vikings put a lot of effort into their appearance. Excavations in Jorvik revealed that finger rings made of various metals, glass, antler, and walrus ivory have been found. These rings made from different materials suggest that the Vikings were connected to Arctic trade routes as well as eastern and western porst.

Throughout Viking Jorvik, archaeologists uncovered a number of security implements. These included found padlocks made of iron in cube and barrel shapes. Archaeologists also excavated keys. These keys were long and thin pieces of metal that could be inserted into padlocks. Decades of excavations show that medieval York was a place where the Vikings conquered the Anglo-Saxons, put down roots, and maintained extensive relations with the outside world. These artifacts reveal that their homes and towns were worth protecting and were essential to unlocking the secrets of Jorvik’s Viking Age.